What? You are going to ROLL my horse?

Non-Surgical Correction of Left Dorsal Displacement with Nephrosplenic Entrapment

Non-Surgical Correction of Left Dorsal Displacement with Nephrosplenic Entrapment

Case Report from Thal Equine LLC January 2015

Friday, an 11-year-old Thoroughbred gelding, arrived at Thal Equine showing signs of abdominal pain (colic). He had not responded to pain relievers and fluids by stomach tube given by the veterinarian at the farm. Upon arrival at our clinic, Friday still exhibited mild signs of abdominal pain; occasionally pawing, stretching and looking at his side. He looked visibly bloated, and he had poor intestinal motility, especially on the left side of his abdomen. While we continued to treat him for pain and dehydration, our most important task was to identify the Condition Causing Colic (CCC), i.e. the diagnosis.

Colic Diagnostics

When a horse is experiencing abdominal pain (colic), it is the veterinarian’s job to identify the underlying cause, the Condition Causing Colic (CCC). Only if we understand the nature of the CCC, can we best identify the treatment options.

Depending on the diagnosis, the appropriate treatment may be simple, such as pain-relief and fluids by nasogastric (stomach) tube. Cases that don’t respond to these treatments might require more aggressive treatment such as hospitalization with IV fluids and ongoing pain relief and careful monitoring. About 5-10% of horses showing signs of colic require colic surgery.

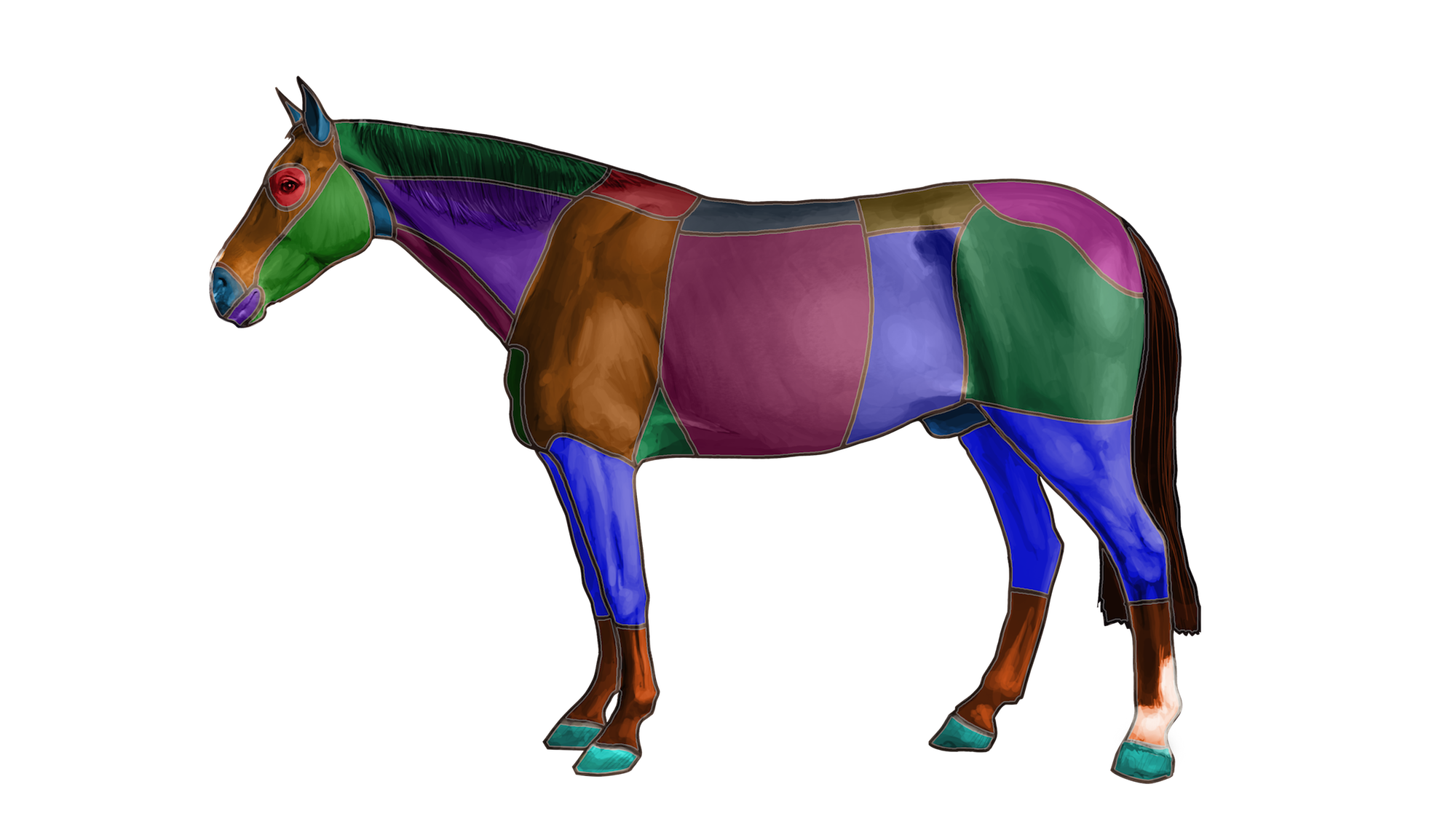

The colic exam is a special physical exam veterinarians do to look at certain aspects of the horse’s health that reflect the intestinal and cardiovascular systems. It considers the complex anatomy and function of the 30-meter (100 feet) long equine gastrointestinal tract. The goal is to determine which anatomic region(s) are affected, and how. We also also use a group of standard diagnostic procedures and tests to gather more information and reach a diagnosis (or at least have a better understanding of the problem) so that we can recommend the most appropriate course of treatment. The amount of and quality of information gathered during a colic exam depends on the veterinarian’s knowledge and experience, and the diagnostics available. An important factor that we always consider is the severity and duration of the horse’s pain.

The rectal exam is a very important diagnostic test for horses showing colic. The veterinarian inserts their gloved arm into the horse’s rectum and feels the abdominal organs, including the regions of intestine, through the thin rectal wall.

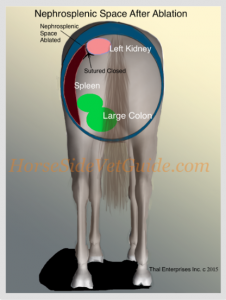

In Friday’s case, the results of the rectal exam were abnormal. We could feel the left colon caught in the space between the kidney and the spleen, hanging on the ligament that joins those two organs. Based on this finding, we believed that he was suffering from a condition called Left Dorsal Displacement of the Large Colon, with a Nephrosplenic Entrapment. Only a small percentage of horses suffering from colic have this condition.

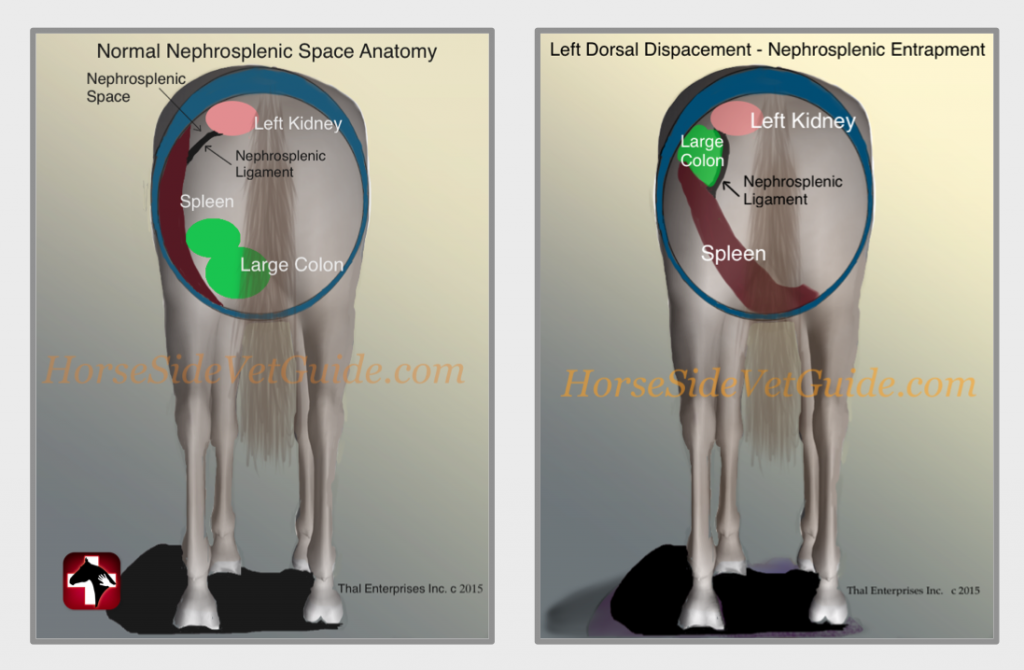

What is a Left Dorsal Displacement with Nephro-Splenic Entrapment?

In a normal healthy horse, the spleen rests against the left abdominal wall and is connected to the left kidney by a short, thick sheet of connective tissue, called the nephro-splenic ligament. Sometimes, however, the very mobile, left part of the large colon (a bulky double horse-shoe shaped organ that weighs about 100 lbs) slides between the spleen and the body wall (called a left dorsal displacement), and can further become entrapped on top of this ligament, within the nephro-splenic space. When the colon is trapped in this position, it is known as a “nephrosplenic entrapment”.

No one really knows why this or many other intestinal displacements take place in horses. In this case, the prevailing wisdom is that abnormal movement (motility) of the colon causes dysfunction and gas accumulation within the colon, which then floats up or is pushed up into the abnormal position. Another hypothesis is that a feed impaction starts the abnormal movement of the colon.

Abdominal ultrasound is another very useful test for supporting this diagnosis. In this case, we used abdominal ultrasound to help us visualize the left upper region, and this confirmed our diagnosis. Friday’s spleen could not be seen in its usual position against the body wall. In fact it was pushed well over to the right of his abdomen, and his left kidney was hidden behind a gas and feed-filled colon.

Treatment Plan – Jog, Roll, or Surgery?

In many cases of intestinal displacement, surgical correction is required. In some “mild” displacements, medical therapy (IV and oral fluids and nursing care) may allow the colon to move back into position. But when we diagnose nephrosplenic entrapment, we usually try one of several special treatments to get the colon unhooked from the ligament.

One common approach to correcting a nephrosplenic entrapment is sometimes called the “drug and jog” approach. A veterinarian administers medication (phenylephrine) to shrink the spleen, and then the horse is jogged and exercised for about 10 minutes. The theory is that this movement helps to jostle the colon back into its proper position. Although some veterinarians favor this approach, and it has been reported to have a high success rate in the veterinary literature, I personally have had mixed results with it. But I do often try this approach first because it is easy. If correction does not take place within a very short period of time though, I move on.

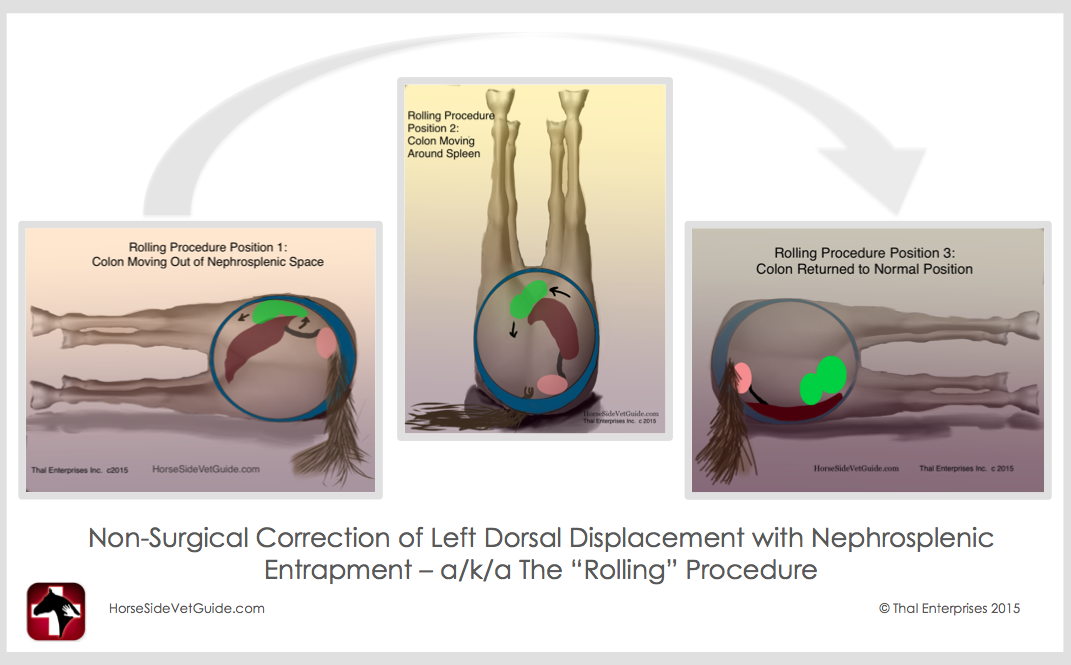

In Friday’s case, the “drug and jog” approach did not work, so I recommended the rolling procedure next. The “Rolling Procedure” is a non-surgical treatment that, when performed correctly, is thought to return the colon to its proper position within the abdomen in about 70% of cases. In our practice, the rolling procedure has been a great tool for treating nephrosplenic entrapment.

Before we performed the rolling procedure on Friday, I was careful to explain to his owner the potential limitations and complications of the procedure:

-

• There is a very small risk associated with short-acting general anesthesia and recovery.

-

• In some cases, the rolling procedure simply does not work. The colon stays trapped and must be manually repositioned at surgery.

-

• In some cases, other intestinal problems are also present. These are not helped by the rolling procedure and so they persist.

-

• There is a small chance of rupture of the tight, distended colon as the abdomen is jostled around.

-

• In rare cases, this procedure may actually convert the simple entrapment of the colon to a twist. In these cases, the horse becomes more painful, and we immediately proceed to colic surgery if it is an option.

The procedure for this disease is really interesting. I wouldn’t have thought that just by rolling the animal would help the organs on the inside. I am curious to know if this is a procedure that horses often get, or if it is really rare, because I have never heard of it before. http://www.dbvh.ca

Very precise description of this procedure. Awesome to know that the success rate is so high, avoiding the cost and risk of surgery !